NGen November 27, 2018

Few things stir fear of the future as much as the predictions of an impending takeover of human work by robots.

It’s a dystopian vision in which smart machines do all the work (including things like writing blogs), leaving people with little to do other than be bored or get into trouble.

The alarm over automation has produced a wide range of reactions. Some people make a considered case for taxing robots to cover the social cost of lost jobs. Others opt for direct action against the machines, like the reports earlier this year -- in San Francisco of all places -- of people attacking self-driving cars in the streets.

The numbers in these early years of the robot revolution hardly seem worthy of mass panic. The recently released 2018 report by the International Federation of Robots says the number of industrial robots has indeed more than doubled in the last five years, jumping by more than 30 percent last year alone with 381,000 units shipped worldwide. That means there are now more than two million robots “working” around the world. Yet this boom in technology adoption has coincided with a period of low unemployment in which the major worry is about a shortage of skilled workers. The rise of the robots has coincided with one of the tightest

The numbers in the Federation’s latest annual Industrial Robot Report should, however, because for at least some unease among Canadian manufacturers. Canada added more than 4,000 new robots in manufacturing in 2017, a healthy 71% increase over the year before.

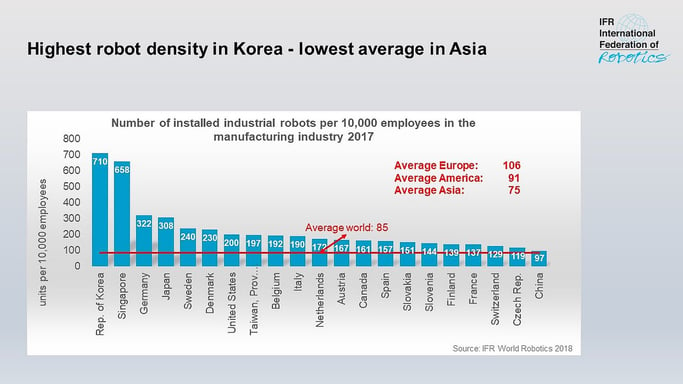

But we still rank just 13th globally for the number of installed robots per employee in manufacturing, with 161 robots in place for every 10,000 manufacturing workers. That’s well behind the global leaders in robot adoption. South Korea leads with 710 installed robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers. Other manufacturing powers like Germany and Japan are also well ahead of us, as are the Americans with 200 robots per 10,000 workers (the global average is 85).

The Federation’s report shows the automotive sector remains the biggest worldwide user of industrial robots, pushed by post-2008 recession restructuring into greater automation. The sector accounts for fully one-third of the world’s installed robots and it’s the sector that drove the 2017 bump in robot adoption in Canada. But the use of robotics is growing across global manufacturing sectors.

The electronics and electrical sector

What’s the right response?

No one should suggest that the shift to more automated

But workers haven’t surrendered control of the factory floor just yet. Another recent study done by the consulting firm A.T. Kearney shows that despite the recent robot invasion, 72% of manufacturing tasks are still done by people.

“Humans still run the show, and will for a long time,” writes Prasad Akella, who led the General Motors collaborative robotics team in the 1990s and who now runs Drishti, a San Francisco-based artificial intelligence startup that seeks to apply data to “extend the human potential in an increasingly automated world.”

So just as the liftoff in global robotics should be a wakeup call to Canadian manufacturers, let’s not miss the accompanying warning that more automation is going to require nurturing a human workforce with the skills and education to exploit all those machines doing the mundane tasks we’ve left behind.

That’s the real lesson for any political and policy leaders: focus on developing the human talent and skills required to run a digital economy. It’s a far better response to the arrival of robots than slapping a self-driving car.

Bruce Wallace

Chief Creative Officer

Next Generation Manufacturing Canada